Backed into a corner without a clear escape route and little-to-no support, a man can react in any number of ways. He can grow violent; he can cower and crumble; he can offer appeals for reason. Or he can shout in defiance of the powers that forced him into the corner in the first place. This last strategy is the one favored by Henrik Ibsen’s Dr. Stockmann of AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE when the powers of politics and society raise up their pitchforks and torches in order to silence his deepest convictions.

Backed into a corner without a clear escape route and little-to-no support, a man can react in any number of ways. He can grow violent; he can cower and crumble; he can offer appeals for reason. Or he can shout in defiance of the powers that forced him into the corner in the first place. This last strategy is the one favored by Henrik Ibsen’s Dr. Stockmann of AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE when the powers of politics and society raise up their pitchforks and torches in order to silence his deepest convictions.

The manic energy of Boyd Gaines’ many shouts defines the core of the Manhattan Theatre Club’s current Broadway production of Ibsen’s play: urgent, forceful, occasionally a bit meandering, but at all times vigorous. Fueled by Rebecca Lenkiewicz’s crisp new adapted script, the production as a whole moves with a briskness that struggles nonetheless to keep pace with Gaines’ kinetic Dr. Stockmann. The discrepancy suits the play well, as Stockmann finds himself often in the position of trying to rush his sluggish town along the path of progress, and Doug Hughes’ direction smartly sets Stockmann in energetic relief of the other characters. To stage AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE in any context is of course to test its lasting relevance against existing social and political power structures, and this production not only suggests that Ibsen remains timely, but also underscores the play’s urgency, as if trying to grab its audience by the shoulders and shake.

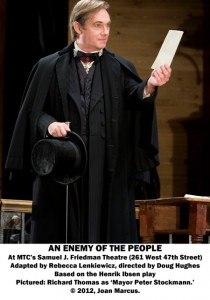

Ibsen’s 1882 semi-autobiographical parable about one man standing alone against the rising tide of politics and public opinion opens as Dr. Stockmann receives confirmation of the suspicions founding his year-long study into his spa town’s prized baths: the very water that is purported to have healing powers is contaminated by pollution at its source. The pipes need to be rerouted entirely, he says, a necessity that will cost the town exorbitantly. Naively expecting that he’ll be greeted with honor and gratitude, Stockmann is aghast when the mayor (Richard Thomas)—who also happens to be his brother Peter—reacts with skepticism, hesitancy, and efforts to silence the doctor’s findings.

A bitter power struggle fueled by politics, money, and fraternal tension ensues as mayor and doctor race to seize the power of public opinion. The doctor getting his way means a great expenditure for the town as well as a glaring black eye for Peter who was instrumental in the planning of the baths. If the mayor gets his way, Dr. Stockmann must turn away from his scientific and moral ideals in order to fall in line behind the interests of politics and money. Over the course of the play, we watch as the brothers’ battle tests the mettle of the townspeople harboring any number of their own political ideals. As allegiances begin to shift or simply crumble we begin to see much more clearly through the expansive gaps in supposedly solid conviction.

A bitter power struggle fueled by politics, money, and fraternal tension ensues as mayor and doctor race to seize the power of public opinion. The doctor getting his way means a great expenditure for the town as well as a glaring black eye for Peter who was instrumental in the planning of the baths. If the mayor gets his way, Dr. Stockmann must turn away from his scientific and moral ideals in order to fall in line behind the interests of politics and money. Over the course of the play, we watch as the brothers’ battle tests the mettle of the townspeople harboring any number of their own political ideals. As allegiances begin to shift or simply crumble we begin to see much more clearly through the expansive gaps in supposedly solid conviction.

Reliant as it is upon the tension between brothers, AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE demands powerful presences from its two leads, and the Manhattan Theatre Club has got that in Gaines and Thomas. While each crafts his own cohesive character, the mayor and doctor are accented strongly by the performers complementing their respective energies. Thomas meets Gaines’ kinetic motor with a stoic, calculated carriage distinctive of a careful politician. Gaines’ doctor is excitable, eager for discovery, and invigorated by progress; Thomas’s mayor is for the most part calm, purposeful, and astutely aware of how his words are to be received by his audience.

Mayor Stockmann is crafty and manipulative in his rhetoric, and Thomas embodies well all that often gives us the creeps about politicians. He shows us clearly the mayor’s confidence in his ability to find the precise string of heart, conscience, or self-interest to tug in order to sway support—and his patience to convince one citizen at a time if he must. While the mayor sees the entire chess board and knows how to navigate it effectively, the doctor strikes at impulse, existing in each moment. Gaines’ Stockmann (whose energy managed even to outrun and thwart his own entrance applause on Saturday) seems ready to bounce off the walls of John Lee Beatty’s beautiful sets and anything else that would try to contain him—kicking off his shoes in the opening scene seems like a self-conscious effort to slow himself down. He is a man of immediate and certain action, a quality that he slowly comes to realize is not shared by the masses. Doctor Stockmann does not waiver in his purpose, but as the play progresses, Gaines’ voice grows steadily louder and more tremulous in response to his character’s growing confusion and disbelief at what he finds to be a weakness of character in those around him.

The vigor of Doctor Stockmann’s energy can be quite funny, a quality that Gaines and Hughes regularly play for laughs. The production skillfully finds plenty of lighthearted moments—especially in Gerry Bamman’s Aslaksen, an elderly liberal idealist with questionable nerve for the fight—but they are not always wisely chosen. The powerful scene in the local newspaper’s print shop forms a crux of the play’s drama. It is when we and Dr. Stockmann first see the conviction of characters that seemed so stalwart hitherto wobble under the weight of the mayor’s rhetoric, and the play’s first indication that political allegiances can be as fickle as the people who pronounce them, but the lighthearted mode in which Hughes presents the scene threatens to undercut its most biting critique. Sadly the effect, which creeps into the scene of Dr. Stockmann’s famous rant as well, is occasionally to convert critique into caricature.

The lasting and most persistent relevance of AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE is its harangue against the voices of ideological masses, and so our recent history’s sharp increase in ideological polarization gives the play an urgency of insight from which the Manhattan Theatre Club does not shy. The stage for Dr. Stockmann’s rant is made shallow by a downstage wall, and the scene plays to and implicates the audience in its drama. The scene and the production suggest that the doctor’s shouts resound beyond the confines of the stage and the play, and into the larger social context. Brisk, clear, and often insightful, this production embraces AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE’s most lasting and immediate sense of concern at the strength of a majority that would drown out the shouts of a passionate voice of resistance.

AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE

by Henrik Ibsen

Adapted by Rebecca Lenkiewicz

Directed by Doug Hughes

EXTENDED Through November 18th

Manhattan Theatre Club

Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

261 W. 47th Street

New York, NY 10036

212-399-3000

http://www.manhattantheatreclub.com/