In the hands of Athol Fugard, anger, bitterness, and spite become not mechanisms of defense and distancing, but key ingredients in a confessional mode. His characters are most open and most themselves precisely when they are most furious. As such THE TRAIN DRIVER, a boldly penetrating if occasionally uneven play about a man hunting down a ghost, becomes an exercise in deep and painful introspection. Because Roelf Visagie, its title character, is mighty angry.

In the hands of Athol Fugard, anger, bitterness, and spite become not mechanisms of defense and distancing, but key ingredients in a confessional mode. His characters are most open and most themselves precisely when they are most furious. As such THE TRAIN DRIVER, a boldly penetrating if occasionally uneven play about a man hunting down a ghost, becomes an exercise in deep and painful introspection. Because Roelf Visagie, its title character, is mighty angry.

And who could blame him? All he was doing was his job when a stranger made him an unwilling accomplice in her suicide by stepping onto the tracks with her baby in tow so that mother and child would be crushed by Roelf’s diesel locomotive. He had no input or control over his contribution to the gruesome events and, worse, he had no way of avoiding what he sees as his agency in the horror. And he isn’t taking it well.

With compassion and courage, THE TRAIN DRIVER examines the journey of a life searching for retribution against the nameless and absent other who has altered its course forever. It is a play of anguish and torment that wrestles with the ghosts of guilt afflicting everyday life.

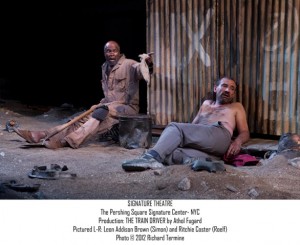

A memory play framed by the prologue and epilogue of its only other character, Simon, THE TRAIN DRIVER opens in the desolate landscape of a South African shantytown cemetery where Simon makes a meager living digging graves for the unidentified and unclaimed dead. A black man who lives in a one-room shack at the cemetery, Simon is unromantic about his work, simply digging graves whenever his boss brings him another nameless corpse, marking the plot with whatever piece of garbage he can find. His solitude and his serenity are jarred by the arrival of Roelf, the white outsider on an apparently senseless mission: he wants Simon to show him the grave of the woman who died under his train so that he might swear viciously at her, unloading all the weight of his anger and guilt in one epically furious tirade. Only then, Roelf believes, will he be able to restore his life to the sanity and calm that have long-since abandoned him.

Simon cannot satisfy Roelf—the graves he digs are far too numerous and nondescript—but he is a patient ear for the outsider to chew with this anger, and gives Roelf shelter from the constant threats of wild dogs and dangerous Amaginsta, violent local youths who Simon knows would murder the outsider on sight (South Africa’s racial politics are less defined here than in some other Fugard work, but they are nonetheless important contributors to the play’s tension). In the time the men share, we watch Roelf’s anger and bitterness evolve through several stages, always uncertain if a dangerous cemetery and taciturn gravedigger will be enough to bring this tortured soul peace.

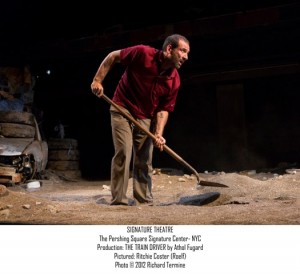

THE TRAIN DRIVER is a two-man play, attended by the presence of countless ghosts and the threat of ever-encroaching offstage forces, ultimately about one man. In a perhaps too-succinct ninety minutes, all the play’s elements work towards developing our introspection of Roelf and his demons. In the glare of such a penetrating spotlight, Ritchie Coster shines. His opening moments are a mélange of exhaustion and fury that bear the weight of weeks searching out the identity of the woman crushed under his train’s wheels (whom he and Simon nickname “Red Doek,” after the head scarf she wore to her death). Coster shows us Roelf as a weary traveler slowly reaching the end of his tattered rope in a desperate attempt to save the final few scraps of his sanity. Roelf’s accent and rage combine to make his language occasionally imperceptible in the play’s opening moments, but he nonetheless shows us this lowly train driver racked by bewilderment and guilt on a poorly contrived quest for vindication.

Our most direct access to Roelf’s torment comes in two long monologues, one initially telling his story to Simon and one later, reflecting on his mindset after some time in the graveyard and shantytown, seeing the desolation in which Red Doek must have lived. These speeches are delivered by two distinct Roelfs—one in the worst throes of anguish, and one progressing slowly and agonizingly out of that torment—and it is edge-of-your-seat enthralling to watch Coster explore his character’s treacherous psyche. Roelf understands neither of these mental states fully, talking himself through and into them with the help first of Simon and then the ghost of Red Doek as sounding boards for his own journey towards understanding. In these confessionals, Coster fearlessly shows us Roelf’s evolving agony laid bare.

Our most direct access to Roelf’s torment comes in two long monologues, one initially telling his story to Simon and one later, reflecting on his mindset after some time in the graveyard and shantytown, seeing the desolation in which Red Doek must have lived. These speeches are delivered by two distinct Roelfs—one in the worst throes of anguish, and one progressing slowly and agonizingly out of that torment—and it is edge-of-your-seat enthralling to watch Coster explore his character’s treacherous psyche. Roelf understands neither of these mental states fully, talking himself through and into them with the help first of Simon and then the ghost of Red Doek as sounding boards for his own journey towards understanding. In these confessionals, Coster fearlessly shows us Roelf’s evolving agony laid bare.

Sadly, Fugard’s penchant for dramaturgical efficiency seems to have cost us a glimpse at Roelf’s transition. We are intimately acquainted with his distinct turmoil at the play’s opening and closing, but we see disappointingly little of the process of that turmoil’s evolution. Similarly, the play leaves the depth of Leon Addison Brown’s Simon largely unexamined. It is not until his epilogue, when Simon brings the memory play’s narrative to a reflective close, that Brown has much of an opportunity to develop Simon.

Doubling as the production’s director, Fugard makes inventive use of the theater’s unique space. The Signature’s Linney Courtyard Theatre is only about seven rows deep, but four or five times as wide, with its large stage that stretches the full width of the theater made more imposing by the room’s intimacy. For Simon and Roelf’s early exchanges, Fugard places his actors almost at opposite extremes of the stage’s width, so as their words volley back and forth the audience’s heads must swivel like at a tennis match. Almost paradoxically, the effect intensifies the early tension, as the two square off from opposite corners, Roelf demanding Simon’s help and the gravedigger trying futilely to avoid engaging the stranger’s crazed quest. At night, the two huddle into Simon’s center-stage shack, and the great distance between these racial and cultural others evaporates as they are forced to share shelter from the violent night.

All this happens in the space of Christopher H. Barreca’s gorgeously stark set. Flirting with the post-apocalyptic, the stage features only a burnt out car and Simon’s shanty, with the entire playing space covered by a thick layer of sandy dirt, mounded in the places where Simon has buried nameless bodies. The theater’s intimacy forces its audience into this cemetery, one which Barreca’s set suggests is far vaster in both space and magnitude than we can see.

All this happens in the space of Christopher H. Barreca’s gorgeously stark set. Flirting with the post-apocalyptic, the stage features only a burnt out car and Simon’s shanty, with the entire playing space covered by a thick layer of sandy dirt, mounded in the places where Simon has buried nameless bodies. The theater’s intimacy forces its audience into this cemetery, one which Barreca’s set suggests is far vaster in both space and magnitude than we can see.

Powerful despite its unevenness, THE TRAIN DRIVER treads fearlessly into the barren terrain of anger in search of the revelations that may lie on the other side. As Roelf and Simon never leave the graveyard, the darkness of the play’s theme never departs, but there are at least glimpses of the productive power of wrestling with despair. Roelf’s peace of mind, like Red Doek’s, remains always in question, but THE TRAIN DRIVER is far more interested in examining his harrowing journey than it is at arriving at that journey’s uncertain destination.

THE TRAIN DRIVER

Written and Directed by Athol Fugard

August 14 – September 23, 2012

Signature Theatre Company

The Pershing Square Signature Center

480 West 42nd Street

New York, NY 10036

212-244-7529

http://www.signaturetheatre.org/