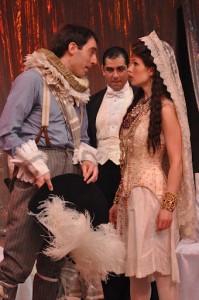

(l-r): Janie Brookshire (Ann) and Max Gordon Moore (as Jack) in George Bernard Shaw's MAN AND SUPERMAN at Irish Repertory Theatre (132 West 22nd St.), directed by David Staller. Photo by James Higgins. For more information, visit http://www.irishrep.org

For all of his sardonic wit and socialist ideals, George Bernard Shaw remained ever amused at the vain triviality of humans. Behind that imposing beard and penetrating gaze must have lurked an at least semi-permanent smirk as he thought, with Puck, “What fools these mortals be.” That spirit underwrites and enlivens every aspect of The Irish Rep’s stellar MAN AND SUPERMAN, a production that chuckles and smirks along with its playwright in a whimsical investigation of the human spirit.

Written and set at the turn of the twentieth century, MAN AND SUPERMAN shows us the familiar cohort of an English comedy of manners: the idle rich of the upper middle class, obsessed with customs and etiquette, their actions guided at all times by seemingly codified social standards. These are the same people Oscar Wilde had so much fun lampooning, and Shaw is certain to get his shots in at both the lifestyle and the genre. All the essential elements are here: money, manners, a drawing room, a troublesome will, scandal, and of course crisscrossed love affairs.

In Shaw’s kitchen, however, these ingredients combine to create anything but the evening’s standard meal. As the play opens, recently deceased Mr. Whitefield’s will has appointed Roebuck Ramsden— an elder man, committed to the structure and customs ordering polite society—and Jack Tanner—the young author of The Revolutionist’s Handbook and Pocket Companion, determined to “shatter creeds and demolish idols”—dual guardians over his twenty-something daughter Ann. The will confounds all involved, but most of all Tanner, the social revolutionist eternally suspicious of womankind, who unsuccessfully attempts to free himself from this duty before getting wind that Ann may very well be secretly in love with him. This terrifying information causes him to skip town, giving Shaw enough freedom from the space and time of drawing room comedy to let his imagination free on the stage.

Shaw called MAN AND SUPERMAN “a drama of ideas,” and it is through Tanner, the playwright’s dramatic surrogate, that ideas are bandied about most freely. Played with fittingly aloof derisiveness by Max Gordon Moore, Tanner has little patience for the pretenses of his social class, and voices his frustrations often and boisterously. The din Gordon Moore gives to Tanner’s frustrated bombast becomes grating at times, but the character might very well need to grate in order to be fully realized. Tanner’s flight from the threat of romance lands him and his driver in the possession of Mendoza, a Spanish brigadier similarly committed to social reform. Their discussions allow Shaw’s drama of ideas the most expansive space for exploration and insight. Jonathan Hammond is a comic delight as Mendoza, with his ideas of social reform delivered through the filters of a hammed-up Spanish accent and a touch of knowing abandon to the powerful tides of society.

MAN AND SUPERMAN could be staged as the dramatization of a philosophical tract—as in many ways it is—but to do so would miss the humor of Shaw’s cynicism. The Irish Rep and director David Staller do not make this mistake, as the production keeps Shaw’s smirk always close at hand. The expansiveness of the play offers unique challenges, especially to a smaller theater like the Irish Rep, but Staller (artistic director of the Gingold Theatrical Group, a project committed to advancing Shaw’s work and ideas in New York) responds to these challenges in cleverly innovative ways. Staller has incorporated some of the precepts of Tanner’s Revolutionist’s Handbook (written by Shaw as an appendix to the play) into the production, as the characters spend scene breaks taking turns reading aphorisms from it to the audience: “Lack of money is the root of all evil”; “Beware of the man whose God is in the skies”; “The only golden rule is that there are no golden rules,” and so on. Similarly added to the script are scenic descriptions by Mrs. Whitefield: “Well, as you can plainly see, this is a lovely tree-lined road which leads to the extremely impressive Whitefield country estate.” Purists might bristle at the additions, but the effect playfully reminds us that theatrical convention is as much a plaything of MAN AND SUPERMAN as customary manners.

(l-r): Max Gordon Moore (Jack/Don Juan), Jonathan Hammond (Mendoza/The Devil), and Janie Brookshire (Ann/Ana) in George Bernard Shaw's MAN AND SUPERMAN at Irish Repertory Theatre (132 West 22nd St.), directed by David Staller. Photo by James Higgins. For more information, visit http://www.irishrep.org

This production’s boldest decision, however, is the inclusion of the rarely performed scene set in Hell. A dream sequence that shows us several of the play’s characters as alter-egos from the Don Juan legend—Tanner as the fabled lover, Mendoza as the devil, among others—this scene was not included in the play’s original staging, and scarcely finds its way into contemporary productions. The exclusion is understandable: the scene is a dry and long-winded philosophical debate between Don Juan and the devil.

This is a rare opportunity to see the Hell scene as part of the play’s whole (often it is performed as a one-act titled DON JUAN IN HELL), and Staller does his best to enliven a distinctly untheatrical scene. Hammond gives the devil a grand sense of freedom and contentment, while Gordon Moore nicely transfers the consternation of Tanner to the intellectual frustrations of Don Juan. As might be expected, Shaw’s Hell is a complete break from convention, and the Irish Rep’s design team (James Noone sets, Kirk Bookman lighting) fully embraces the freedom Shaw offers them: this Hell is the wonderfully gleaming crystalline white so familiar of popular representations of Heaven.

MAN AND SUPERMAN takes its title from Nietzsche, who theorized a superman transcending day-to-day struggles in order to find the greater glory of existence. Although heavily influenced by Nietzsche, Shaw was far more realistic and skeptical, and gives us here an at-times comic, at-times farcical play examining the Nietzschean ideal through the lens of “polite society.” The play is Tanner’s, and we watch as he struggles to keep hold of his revolutionary ideals against the encroaching force of society and, most significantly, of womankind. “Beware the pursuit of the Superhuman,” warns the devil, “it leads to an indiscriminate contempt for the Human.” This play shows us Shaw as seemingly resigned to the realm of the human, and examining with a smirk how best to respond to that reality.

MAN AND SUPERMAN

Written by George Bernard Shaw

Directed by David Staller

April 26 – June 17, 2012

The Irish Repertory Theatre

132 West 22nd Street

New York, NY, 10011

212-727-2737

http://www.irishrep.org/

2 comments

Shaw may have had a perpetual smirk, but “Man and Superman” ultimately places its faith in the “Life Force,” and “creative evolution.” Mr. Maley seems to misunderstand the “Don Juan in Hell” scene; the devil is not the voice of Shaw, but an articulate straw-man he can refute. The following is an excerpt of a review from the blog, “Le Journal de Charles Haas,” the entirety of which cannot evidently be included here:

“Hamlet dramatized the insufficiency of language with characteristic wit and aplomb: “Words, words, words.” In The Irish Repertory’s production of Shaw’s Man and Superman, the word is talk. Midway through the play, Mr. Straker— the kind of earthy chauffeur and engineer who corrects his employer, Jack Tanner (Member of the Idle Rich Class) after he misattributes an epigram to Voltaire when it was, of course, Beaumarchais— comments that, “Garn! I wish I had a car that would go as fast as you can talk, Mr. Tanner.” “We even get a riff of the Shakespearian melancholy line with Jack’s, “Talk! Talk! It means nothing to you but talk.” The play even ends to resounding laughter after Jack exclaims, “Talking!” This litany is not to deny the power of speech. Theatre has the unique advantage of being built on the foundations of language, whereas cinema is grounded in image, but there is a difference between words and talk. And this mild reproach isn’t to say that it isn’t perfectly, pleasant, charming erudite talk, but it is still talk…”

I would invite Mr. Haas to reread this review more carefully.

Nowhere do I claim that the Devil is the voice of Shaw. Instead, I call Tanner “the playwright’s dramatic surrogate,” as he is. Tanner’s frustrations with the hegemony of manners and customs mirror those of Shaw’s, and “Don Juan in Hell” gives those same frustrations to Tanner’s alter ago, Don Juan.

To claim that MAN AND SUPERMAN “ultimately places its faith in the ‘Life Force’ and ‘creative evolution,'” is an unfortunate misreading of the play.

Tanner, like Shaw, ultimately resigns himself to the Life Force, but he is by no means happy about it, and even less so faithful in it. Shaw acquiesced to marriage (after years of kicking and screaming) shortly before writing MAN AND SUPERMAN, and the play shows us the playwright voicing his frustrations with the trademark wit and humor of the sort of man who lived a long life watching those around him struggle with ideals he recognized as foolish.

The play certainly stresses the ephemeral nature of talk, but it does so in a way that underscores a resignation to the overpowering of language and dialogue by a man-made and spuriously codified “life force.”