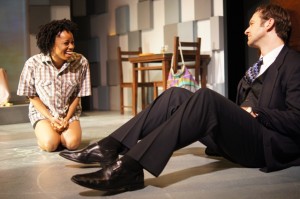

chandra thomas and Steve Kuhel star in THE HISTORY OF LIGHT at Passage Theatre Company in Trenton, NJ through November 20. (Photo credit: Michael Goldstein)

With a consistently bittersweet passion, the Passage Theatre Company’s production of THE HISTORY OF LIGHT makes its audience voyeur to a journey of self-discovery across terrain hazardously defined by other peoples’ affection. Accented by tensions of race, politics, family, and love, Eisa Davis’s play travels through history, memory, and dreams to examine fully the myriad factors preventing its protagonist, Sophia, from knowing who she is and, more importantly, coming to peace with that understanding. In the process, THE HISTORY OF LIGHT shows deep compassion for the tenuous psyche at its center.

Sophia is a thirty-year-old musician and songwriter struggling as an artist in the nondescript “city.” She plays nightclubs, auditions for theater, and, when her unemployment runs out, temps at corporate offices. But her professional struggles pale in comparison to the psychological and emotional disorder of her private life. Moments after the play opens with Sophia performing a revealingly melancholy love song at the piano, Matthew emerges from the audience to say hello—the first hello between the two in ten years. The play’s rapid exposition tells us that these two had been friends from grade school through college, and hints at a turbulent period of romance that ended ten years prior, fatefully on “that night at the airport.” Pleasantries quickly give way to bitterness, as “Soph” makes clear to “Math” that she has not forgiven him, and Math implores Soph for compassion and friendship, while offering no explanations.

And one more thing: Soph is black and Math is white. Interracial love turns out to be THE HISTORY OF LIGHT’s defining structure, as we come to learn that Turner, the father Soph never knew, had a steamy relationship with a white woman in the 60’s before abandoning her for the black woman that would be Soph’s mother. Though she does not immediately know it, Soph thus inherits a legacy of doomed interracial love, the force of which is constantly tested by her increasingly confused relationship with Math. Soph’s struggle to understand her place in the torrent of affection and neglect defined on the one hand by her evolving feelings towards her father, and on the other hand by the puzzling emotions awoken by the return of a long-lost ex-flame, gives this play its most compelling tension.

THE HISTORY OF LIGHT thus demands much of its Sophia, and chandra thomas rises admirably to that call. From the play’s opening moments, Ms. thomas moves Soph nimbly through states of confidence, defiance, weakness, anger, fear, and joy, not only allowing us to see unique emotional terrain, but also granting us access to the transitional spaces between those emotions. Calling Math “a poison, a chronic disease” upon his reappearance in her life, Soph gradually returns to familiar affections for him, and Ms. thomas vividly portrays Soph’s slow, begrudging acceptance of that shift. At times Ms. thomas plays the petulant child, and at others a defiant individual trying to convince herself the she doesn’t need love and acceptance, but these and others emotional states always seem appropriately fleeting and tentative. Soph knows neither who she is nor who she wants to be, and Ms. thomas impressively keeps that confusion and turmoil at the fore.

While less demanding than Sophia, the play’s other three characters each require a range nicely embodied by the rest of the cast. June Ballinger’s Suze, for instance, is Turner’s white girlfriend who appears on stage in either Soph’s dramatized dreams, flashbacks to her relationship with Turner, or as the narrator of letters she writes to Sophia from her current home in France, hoping to help Soph know more about Turner. Suze has had a life fighting through similar existential quandaries as Soph now does, and while Ms. Ballinger gets less opportunity than Ms. thomas to explore emotional transition, she nonetheless succeeds in examining the important points of tension and turmoil in Suze. Similarly, Peter Jay Fernandez plays a young, a dreamed, and a contemporary Turner; he proves most impressive in the play’s latter stages, where his contemporary self faces the challenge of standing always in reference to his prehistory shown in act one. Steve Kuhel is an effectively shallow Math, but his performance is limited by the character’s lack of emotional depth. Much of Soph’s frustration with Math is this very shallowness: he carries himself with a smile and a romantic passion for music and love, but there are hints that below the surface lay struggles of which neither we nor Soph ever get much of a glimpse. “It’s difficult to be in a relationship with me,” Math says at one point, but we are forced to take his word for it.

The play’s scenery is effectively simple and sparse, dominated by a large down-stage piano. Although Soph and Math are in unique and conflicting emotional states, they nonetheless share an unyielding passion for classical piano, a love which THE HISTORY OF LIGHT often shows them sharing. The two seem the most at peace when sitting side-by-side on a piano bench, as if in stark seclusion from their conflicting emotions and diverging life paths. Things get tricky when they must leave that bench in order to conduct their day-to-day lives. When Soph first leaves the piano after her opening number, she gathers her belongings, which include a large, clunky purse. Though the piano may be the play’s most physically imposing prop, this purse stands out as its most poignant. The purse gets heavier and fuller of problems and challenges for Soph as the play progresses. Lugging it from scene to scene, Soph is comfortable neither with the purse nor the pounds of emotional baggage it contains. Only once she physically leaves her purse behind can Soph begin to seek out answers and an understanding for herself, rather than in reference to her cluttered and burdensome past.

Jay Fernandez and chandra thomas in a scene from THE HISTORY OF LIGHT at Passage Theatre Company. (Photo credit: Michael Goldstein)

Challenging realist form and playing with mixed media—the play includes pictures projected on the rear wall and, at one point, a raw egg hurled from the back of the house, over the audience, to smash onto the set—THE HISTORY OF LIGHT achieves both deep pathos and, at times, lovely spells of whimsy. Race and politics prove less the play’s raison d’etre than its backdrop to one woman’s struggle for self-understanding. Rejected by men she’s loved and who are supposed to love her, Soph’s songwriting proves an outlet but not a remedy for her emotional bewilderment. With this struggle as its focus, THE HISTORY OF LIGHT becomes a penetrating and sympathetic examination of the at-times inexplicable need for connection, love, and affection that we social beings all embody.

THE HISTORY OF LIGHT

Written by Eisa Davis

Directed by Jade King Carroll

November 3 – 20, 2011

Passage Theatre Company

at Mill Hill Playhouse

205 East Front Street

Trenton, NJ

(609) 392-0766

http://passagetheatre.org